Can Denmark’s world-beating drugs maker stay ahead?

Well-known in business circles, but hardly a household name, Novo Nordisk had not previously been seen as a big player in the drugs industry, let alone a titan of the European stock market.

But it leapt to the top of the league table and was valued at $428bn (£342bn) because it has discovered the Holy Grail of all drugs. One that millions of people want and need across the Western World and beyond.

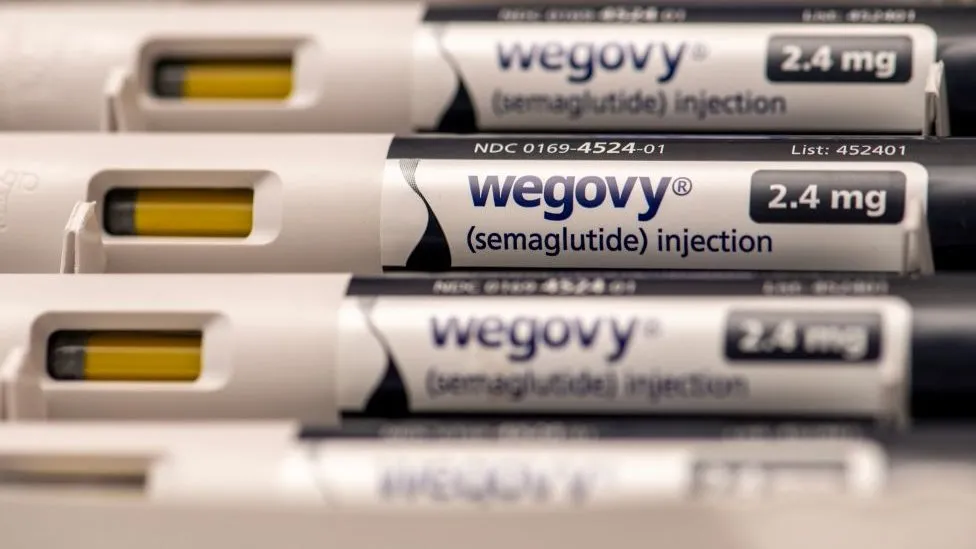

Called Wegovy, its active ingredient was designed to tackle type 2 diabetes, but as a side effect was found to almost guarantee to make people lose weight.

Like Viagra, which was originally supposed to treat high blood pressure, unrealised but popular side effects have made Wegovy a must-have drug.

It is knocking at an open door – Goldman Sachs research predicts that the anti-obesity drugs market is worth some $6bn this year. But by 2030, it could grow by more than 16 times to $100bn.

It almost sounds too good to be true, but what are the long-term prospects and consequences for a pharmaceutical company that discovers a sure-fire winner? Is it really the Midas touch or more of a poisoned chalice?

Well for a start, having discovered a drug that suddenly dominates the market is just the start of the process. You have to make it, market it and negotiate the price with a whole host of health companies and national health services.

Some like the NHS in the UK are so large they can force down the cost and therefore the profitability of even the most popular drugs.

At the moment Wegovy is available on the NHS for weight management in specific circumstances.

Claire Machin is executive director for international policy and UK competitiveness at the ABPI, the body that represents pharmaceutical companies in the UK.

She told me that the UK not only forces down prices for drugs using a value-for-money standard set 20 years ago, but then the NHS will negotiate even lower prices, followed by a further requirement for cash rebates from companies when the NHS exceeds its medicines budget.

“Because of that, the UK spends comparatively less on medicines than similar countries, spending about 9% of its total health budget on medicines, compared to around 14% in Australia, 15% in France, and 17% in Germany.”

Then there are operational problems, In 2022 Novo Nordisk had trouble meeting the huge demand for Wegovy. In December 2023 its shares were marked down because of worries about its ability to produce the drug in enough quantity again, and at a high enough quality, to satisfy the industry’s regulators.

The company admits that in the US, during December it ran out of the 1.7mg dose of Wegovy. That happened despite running its manufacturing lines “24 hours a day, seven days a week”.

But, it expects to be able to restart shipments this month.

Then there is the quite obvious fact that Wegovy’s head start is just that, a head start.

There are already other drugs from other companies that do the same thing. Those companies will be working night and day to improve their drugs, to market them better, to sell them cheaper, and to undercut Novo Nordisk at every chance. After all, there is a potential market of $100bn a year at stake.

In November, Eli Lilly, an American pharmaceutical giant got approval for its weight lose drug Mounjaro in the UK. Other alternatives include drugs like Saxenda, Orlistat, and Qsymia – the battle to dominate the weight loss drug market is well under way.

Of course, Novo Nordisk is protected from direct competition by its drug patents that normally run for 20 years. After that anyone can enter the market and make their own generic version of its drug.

Pharmaceutical patents mean companies have to make the money while the going is good. When anyone can copy them the good times are well and truly over.

“I think 90% of pharmaceutical spend in the UK, and I’m pretty sure it’s similar in the US, is for generics… so, you [the original inventor] may well retain market share, but the price will fall,” says Graham Cookson chief executive of the Office of Health Economics, the world’s oldest health economics research organisation.

Then there is one final problem for the discoverer of a giant new successful drug. It makes you stand out from the crowd, and if you are a small or even medium sized company that makes you vulnerable. It really does not pay to be too popular.

Pharmaceutical giants have very deep pockets and if their extensive and expensive drug development programmes have failed to find the best drugs there is a simple solution, buy the company that has.

But Novo Nordisk has one final card up its sleeve, most of its shares are owned by a Danish Foundation, making it virtually immune to a takeover bid.