They might seem like disparate worlds, but throughout history, fashion and political activism have gone together. Campaigners have long recognised and wielded the power of clothes, from the suffragettes sweeping through the streets in white dresses to their second-wave sisters famously binning their bras. However, no group has better understood how to channel personal style for political gains than the Black Panthers, the radical political party formed during the US civil rights movement, known for its instantly recognisable military-like uniform. The group’s signature black beret held particular symbolic weight – co-founder Huey Newton was said to have been inspired to wear it by a film about French Resistance fighters. He described the party’s accessory of choice as “an international hat for the revolutionary”.

The worldwide Black Lives Matter protests that followed the killing of George Floyd earlier in 2020 have sparked renewed interest in the Black Panther Party and its dress codes, as campaigners today look to movements of the past. British Vogue’s September issue, which was dedicated to “activism now”, saw supermodel Adwoa Aboah appear on the front cover dressed all in black, her beret a clear nod to the Panthers, while dancer and presenter Ashley Banjo later appeared in British GQ in a similar outfit. At marches too, protestors could be spotted in clothes that harked back to those worn by the likes of Fred Hampton and Kathleen Cleaver.

This revival of the Black Panther look not only points to an embrace of the more radical politics that the party championed, but also an understanding of how clothes can be used to further the cause. “When you see Black Panther Party members in the all-black ensembles, it sends this message of unity as well as conveying a powerful statement through photography,” fashion historian Darnell-Jamal Lisby Culture. “It’s similar to the suffragettes… Everyone was fully aware of the impact.”

Fifty-four years on from the party’s founding, amid scenes of police brutality that are eerily reminiscent of the 1960s, the sense of urgency among black people has been encapsulated in the slogan T-shirt, in some ways the unofficial uniform of today’s activist. In 2020, celebrities and athletes have joined grassroots campaigners in sporting shirts emblazoned with punchy, powerful statements: basketball star LeBron James in “I Can’t Breathe”; actor Sterling K Brown in “BLM” and a Black Power fist; racing driver Lewis Hamilton demanding that authorities “Arrest The Cops Who Killed Breonna Taylor”; British football teams in various anti-racist slogan T-shirts.

While clothes have long been viewed as a tool for communication, the BLM slogan T-shirt eschews subtlety, delivering its message instead with blunt conviction. For some, it’s simply a show of solidarity; for others, it’s about forcing people to face up to the pressing issues, using whatever platform you might have. “[Slogan T-shirts] can be worn in day-to-day life – the protest can resonate not only during a march but also when you’re at a grocery store or getting your hair cut,” says Lisby.

Even for those who consider what they wear to be entirely apolitical, the huge international industry behind our clothes has long been tied up with wider issues, from workers’ rights to the climate crisis. And this year, the ripple effect of George Floyd’s killing forced the fashion industry – like many others – to respond. Not long after protests erupted in Minneapolis and spread like wildfire, brands rushed to express their support, releasing statements, announcing donations to bail funds, and selling slogan T-shirts. Probing the role they may have played in upholding – and often perpetuating – structural racism, however, has proven somewhat trickier.

After years of glacial progress, a number of initiatives striving to tackle racism in fashion have sprung up within months. Among them is the Black in Fashion Council, launched in July by Teen Vogue editor-in-chief Lindsay Peoples Wagner and fashion publicist Sandrine Charles, with a mission to “represent and secure the advancement of black individuals in the fashion and beauty industry”. In a widely shared article edited by Wagner for The Cut in 2018, dozens of black people working in fashion spoke of micro-aggressions, fetishisation, tokenism and difficulties ascending the career ladder.

Long-lasting change

“Fashion is very elitist, and people tend to get employed when they look like the people that are already in those positions,” says Bemi Shaw, a London-based stylist who has worked on photo shoots with stars such as singer-songwriter Jorja Smith and designer Victoria Beckham. Before this year, much of the conversation around race within fashion was centred on the need for more diverse models – the most visible faces of the industry, albeit not the ones pulling the levers of power. Through its directory of black editors, stylists and executives, as well as its equality index that scores companies on inclusivity, the Black in Fashion Council is striving to shake up an industry that still favours those who are thin, wealthy and white.

While some of fashion’s most prestigious brands are now scrambling to save face, British Vogue has emerged as a beacon for the industry. When Edward Enninful, the son of Ghanaian immigrants and the first black editor-in-chief in the magazine’s history, took the helm in 2017, he spoke of his desire for his Vogue to be inclusive – the previous editor had drawn criticism for the dearth of black cover stars and an all-white workforce.

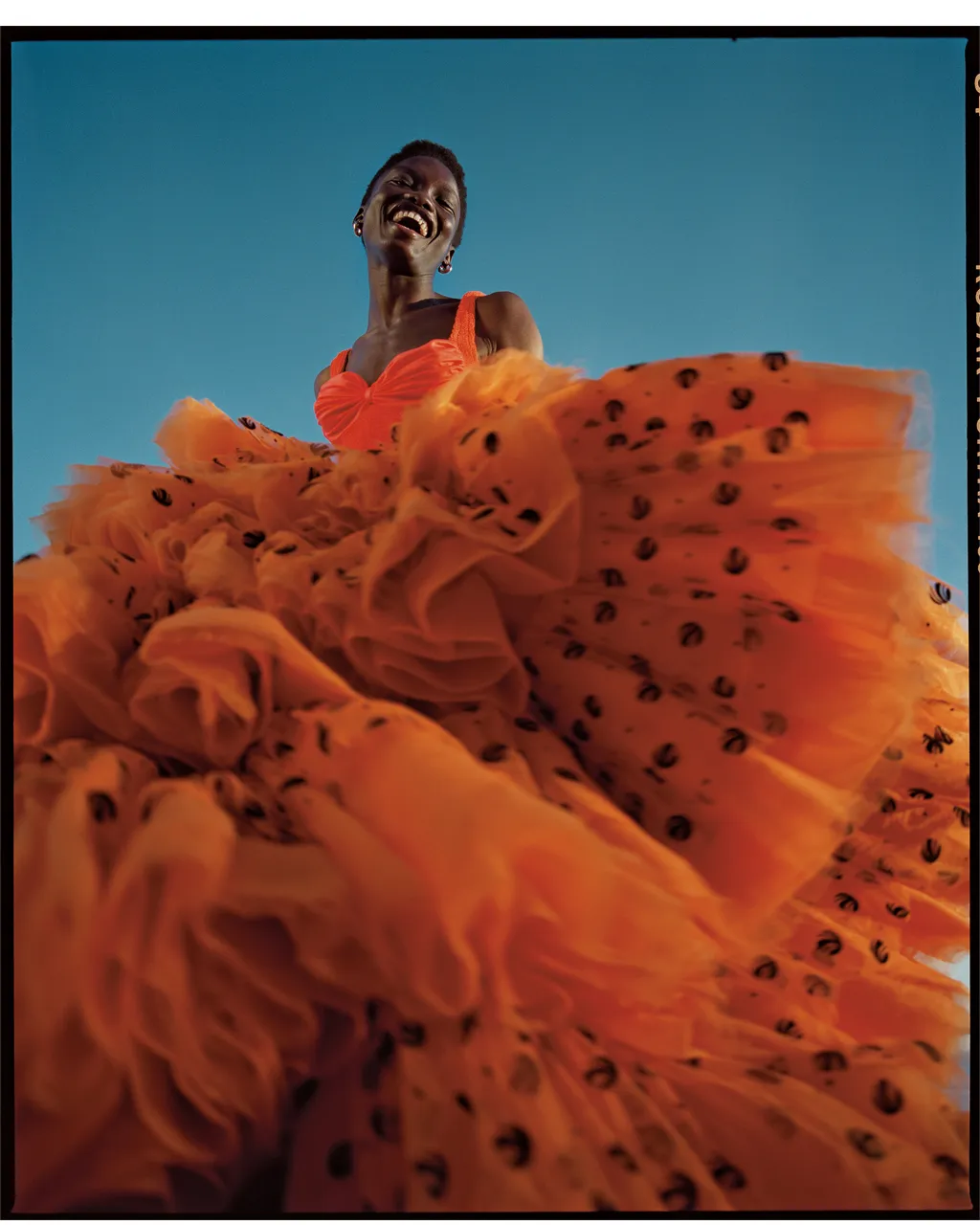

Alongside the magazine’s September issue that spotlighted black activists, 2020 alone has seen cover stars including Serena Williams, Rihanna, Beyoncé and Lupita Nyong’o. The Vogue website offered extensive coverage of the protests, and now has a dedicated anti-racism section, while people of colour make up a quarter of staff. As Diana Evans writes in her profile of Enninful for Time, “British Vogue has morphed from a white-run glossy of the bourgeois oblivious into a diverse and inclusive on-point fashion platform”.

Attuned to the importance of capturing their increasingly diverse cover stars outside of a white gaze, British Vogue has also begun commissioning black fashion photographers, who, until recently, had been virtually invisible. (In December 2018, Nadine Ijewere became the first black woman to shoot the cover of any Vogue, ever.) This year, Enninful and his team have tapped lesser-known names like Misan Harriman, who captured some of the defining images of the London protests, as well as 21-year-old Kennedi Carter, whose work seeks to highlight the “overlooked beauties of the black experience”.

In an industry that still suffers from ‘snowy peaks’, uplifting black creatives in fashion often means taking the time to seek out and nurture new talent, rather than relying on the usual go-to names. “It’s just about not being lazy, because there is so much talent out there,” says Shaw. “Where we stand in fashion at the moment, it’s so stagnant because it’s the same eight people doing the same thing over and over again.”

Shaw herself is keen to pay it forward in her own work by championing black designers too. “I love when I get an editorial opportunity and I can put people on that wouldn’t necessarily have got that light to shine,” she tells BBC Culture. This year, designers who’d long been overlooked have suddenly been thrust into the spotlight as the Black Lives Matter movement encouraged the support of black-owned businesses. In the US, accessories designer Aurora James launched the 15 Percent Pledge, asking retailers to ensure 15% of their stock come from black-owned brands, in line with the African-American population.

Fashion buyers who commit to the pledge have a growing contingent to pick from, among them CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund winners Christopher John Rogers and Kerby Jean Raymond. Many of these designers are not just creating beautiful clothes, but rewriting the rules of luxury altogether, shunning elitist, Eurocentric ideals. Jewellery designer Jameel Mohammed’s pieces draw inspiration from West African masks and the horns of Kenyan cattle, while Telfar Clemens’s accessibly priced ‘Bushwick Birkin’ has shown that an It-bag needn’t be exclusive.

2020 has undoubtedly felt like a watershed moment. But fashion is a famously fickle industry, and the sudden rush to stand against racism after decades of helping perpetuate it has left many sceptical. “Honestly, I didn’t keep up with it because so much of it felt so deeply performative,” says Aja Barber, a fashion activist whose work focuses on making the industry more inclusive and sustainable. “Black Lives Matter has been a movement for years. Why is it only socially ‘acceptable’ now?” Likewise, there have been debates around the role of T-shirt activism, seen by some as an exercise in ‘virtue signalling’ that allows one to outwardly express solidarity while doing little to effect real change. (Breonna Taylor’s killers were not charged over her death, and the once-ubiquitous slogan tee about her has now been consigned to the back of the wardrobe.)

As 2020 draws to a close, and #BlackLivesMatter is no longer trending, it remains to be seen whether fashion’s support for the movement goes beyond publicity statements and politically charged T-shirts. As Barber succinctly puts it: “The fashion landscape will have long-lasting change when power is passed from the hands of those who have traditionally held it to those who have not.”