What made Maria Callas the world’s ‘greatest diva’

This month marks the centenary of one of music’s most illustrious artists: Greek-American opera soprano Maria Callas, born Maria Kalogeropoulos in Manhattan, December 1923. Callas earned the sobriquet “La Divina” over a relatively brief singing career that projected her technical brilliance, passion and expressive flair to the world. She also bore the crushing pressures of that status, and was just 53 when she died of a heart attack at her Paris home. Many of the 100th anniversary events are invariably epic in scale, including Unesco celebrations across iconic Greek landmarks, and a wealth of music reissues. Yet Callas’s legacy remains powerfully intimate, too.

A new documentary explores the highs and lows of Callas’s life, as well as what her legacy is today. “She worked so hard, she made herself Maria Callas – she made herself the greatest diva,” Stella Kourmapana, archivist at the Athens Conservatoire, explains in Maria Callas, part of series Take Me to The Opera.

Callas united so-called high culture and pop culture, without compromising her repertoire. Her performances caused a clamour at world-class institutions including Milan’s La Scala and New York’s Metropolitan Opera, and she collaborated with the likes of Luchino Visconti, Franco Zeffirelli and Leonard Bernstein, as well as Pier Paolo Pasolini (who cast her in the non-singing title role of his 1969 movie Medea, some years after her final concerts). She was also beamed to prime-time TV audiences, such as her 1956 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show,where she sang Vissi d’arte (I lived for art), an aria from Giacomo Puccini’s 1899 opera Tosca.

Certainly, Callas’s private life drew heightened levels of mainstream publicity and intrusion, intensified by those who should have protected her but exploited her talents instead, including her parents and sister; her much older husband; her lover Aristotle Onassis (who would eventually marry Jackie Kennedy, but continue to pursue Callas). Such dramas – and her transformation from “ugly duckling” to fashion siren with flashing eyes and dazzling jewels – have fuelled decades of gossip columns and biographies. Ultimately, even Callas’s trolls are struck silent by her voice: captivating rather than simply pretty; fiery, imperious and tender in turn.

The defining diva

The image of Callas as an archetypal diva, and the notion that the goddess-star should suffer for her art, is loaded; there is no equivalent that positions a male divo on quite the same pedestal, or exposes them to the same judgements. Yet Callas did arguably channel real-life trauma and conflict into her musical delivery, and seemed bound by the notion of “destiny”.

Her exacting standards underpinned a high-maintenance reputation; she also made no secret of her impoverished upbringing or early career. “Be careful when you say ‘ghetto’… music comes from there,” she told French journalist Philippe Caloni in her final interview (1977). “I’ve almost never seen a great musician who had an upper-class background. There’s something good about ghettos because if you come from there, it makes you want more. It makes you say, ‘One day I’ll be someone’.”

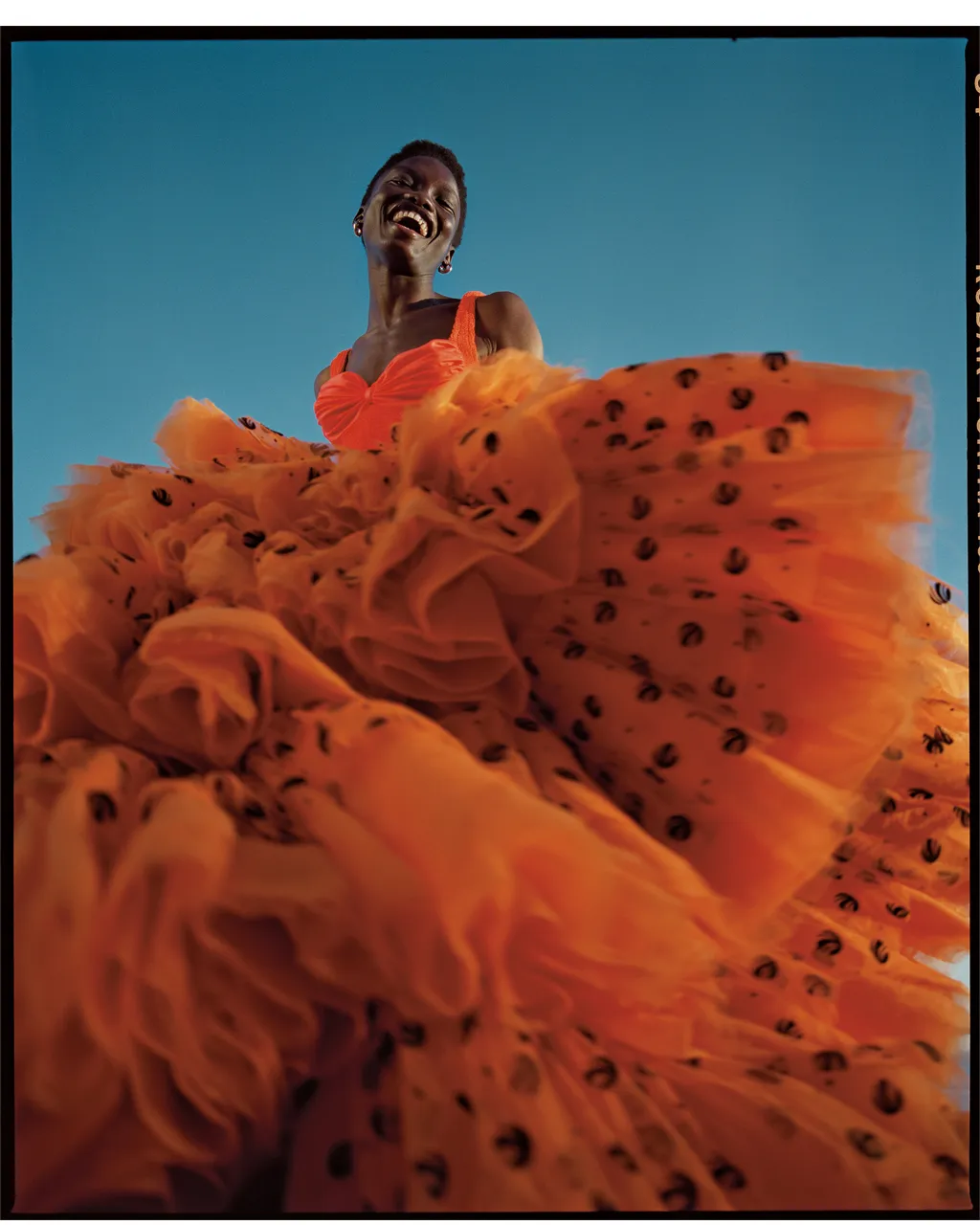

Callas is featured in a major group exhibition, Diva, at London’s V&A Museum until April 2024; the show reframes the “diva” concept, from 19th-Century opera stars to contemporary A-listers, with highlights including costumes from Callas’s final performance at the Royal Opera House, as well as legendary recordings. Exhibition curator Kate Bailey explains: “Callas sits as this kind of personification of ‘diva’ at a particular moment in time; in the mid-20th Century, you have this emerging second wave of feminism, where the ‘diva’ explodes into other music genres, but also draws from the 1830s, because she really made that whole style of [bel canto] singing fashionable again.

“It was almost written in the early diva narrative that you would perform this extraordinary operatic role to take you to the depths of your emotion – and then you die on stage. That is rooted in the diva concept of fragility, vulnerability – and if you’re reclaiming this and reshaping things as a pioneer, there’s a struggle to get there,” Bailey tells Culture.

“The media scrutiny, the fashion and the tragedy were really on a whole other level with Callas – but she was so dedicated to the best of her art; it was commitment and hard graft, married with ambition and motivation. People would queue for miles to see Callas, and hear her unamplified vocals. Today, we do the same with Beyoncé, because of her stage presence – but it’s Callas’s power of music and empathy that really takes it to an emotional level.”

Many of the ordeals that Callas faced have been replayed over generations of female stars: censure towards a strong woman knowing her worth; female talents pitted against each other (Callas had a much-publicised feud with Italian soprano Renata Tebaldi); punishing tour schedules, even when she clearly needed time to recuperate from illness or exhaustion.

Callas maintained her poise in the face of astounding cruelty, and long before mainstream notions of artist wellbeing or body positivity; it’s hard to imagine people camping out for Beyoncé or Gaga shows solely to jeer or pelt the stars with vegetables. Derided in her youth for being fat, Callas was later slated for being too thin; her weight loss was said to contribute to her vocal decline, although the intensity and range of her work was surely a factor.

She was undeniably a pioneer, on stage and in the studio; Callas’s recorded repertoire spans her late-’40s work to her latest appearances, drawing multi-generational listeners as close as possible. In September, Warner Classics released La Divina: an expansive box set encompassing Callas in all her versatile roles, including her early-’70s Juilliard student sessions (which also inspired Terrence McNally’s 1995 play, Master Class); a range of coloured vinyl compilations will also be available.

La Divina curator, musicologist and writer Michel Roubinet, is emphatic about Callas’s enduring legacy: “Her voice undeniably engages all the senses at once, speaking to the mind, the heart, and the depths of those who listen,” he says. “It resonates and vibrates, and with her unique manner of placing the word on the note, she brings a subtle and sensitive agogic, breathing even more life into the music and the drama. It evokes emotions including humour, though she sang very little in comedic roles, displaying an irresistible spirit, always with a touch of irony.

“Perhaps Maria Callas, beyond her genius as a musicienne assoluta, so timeless and perpetually modern in the sensory impact it has on the listener, continues to fascinate because she actually has no true descendants.”

The posthumous veneration of Callas might deflect from the media industry’s original malice, but it also reflects her inimitable force. There is only one Callas, yet there are seemingly countless incarnations; as listeners, we project our personal desires, and distresses, onto her expressions – and we continue to bond with her music, in unpredictable ways. Tom Volf, the director of acclaimed documentary Maria by Callas (2017), has described first discovering Callas (in the “mad scene” from Gaetano Donizetti’s 1835 opera Lucia di Lammermoor) on YouTube in the early hours; “The only thing I could see or feel was something incredible, indescribable, passing through me when I was listening to her,” Volf told NPR.

I did not grow up listening to opera music, but Callas also connected through the pop culture of my teens. There was the movie scene in Philadelphia (1993), where Tom Hanks’s character tearfully translates Callas’s aria La Mamma Morta(from Umberto Giordano’s 1896 opera Andrea Chénier): “I am Divine… I am oblivion… I am love!”), or a series of Jean-Paul Gaultier fragrance commercials, soundtracked by Callas singing Casta Diva (one of her most famous renditions, from Vincenzo Bellini’s 1831 opera Norma); I recall thinking how alluring and transformative her music felt.

In the 21st Century, Callas has taken the form of a hologram on tour (though it’s unlikely that the real-life perfectionist star would have approved of the glitchy tech), and been portrayed by actresses including Fanny Ardant (in Zeffirelli’s 2002 biopic Callas Forever) and Angelina Jolie (set to star in Pablo Larraín’s upcoming film Maria).

She also inspired the performance artist Marina Abramović’s opera homage, 7 Deaths of Maria Callas, which made its UK debut with the ENO at the London Coliseum in November. In a 2020 interview , Abramovic described first hearing Callas on a radio broadcast as a teen (“I had electricity and total goosebumps in my body”), adding that she sensed parallels between Callas’s life experience and her own: “And then, also, this incredible intensity in the emotions, that she can be fragile, and strong at the same time.” That sensation never fades; Callas remains relatable and revolutionary: the sound of worlds colliding.